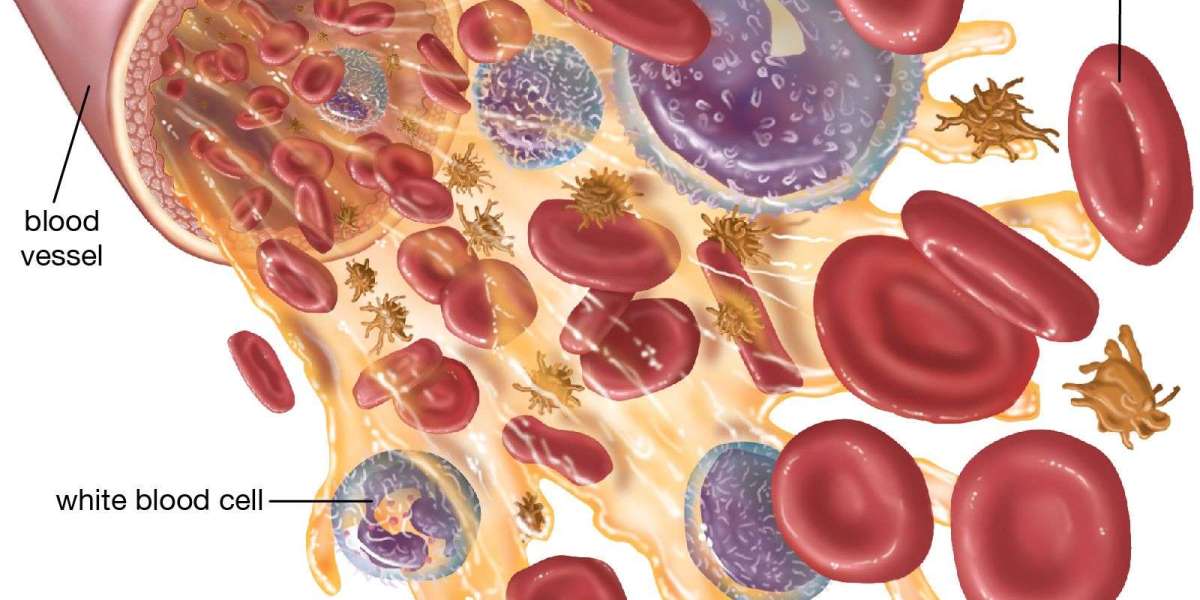

A healthy immune system relies on a robust supply of white blood cells (WBCs) to defend the body against infections. When the level of white blood cells drops below the normal range, it's called leukopenia. In some cases people refer to neutropenia, a low level of neutrophils (the most common type of WBC). Either way, a low WBC count can raise your risk of infections and can be a sign of an underlying health issue. Understanding what low WBCs mean, what can cause them, and what steps to take helps you respond quickly and effectively.

What is a low white blood cell count

- Normal ranges vary by lab, but a typical total WBC count is about 4,000 to 11,000 cells per microliter (cells/µL) of blood in adults.

- Leukopenia is generally defined as a WBC count below about 4,000/µL, though exact thresholds can differ by lab and age.

- A complete blood count (CBC) with differential provides not only the total WBC count but the numbers of the major WBC types: neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils. Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) is especially important when assessing infection risk. An ANC below roughly 1,500/µL is considered neutropenia; below 500/µL is severe neutropenia.

Why low WBCs matter for your health

- Infection risk rises: White blood cells are your frontline defenders. Fewer of them mean infections can start more easily or become more severe, even with minor exposures.

- Subtle or atypical infections: People with low WBCs may not have the usual fever or obvious symptoms. Infections can progress quickly, so vigilance is important.

- Delayed healing: In some cases, wounds and injuries may heal more slowly when the immune response is weakened.

- Signals of an underlying problem: A low WBC count isn’t a disease by itself it’s a sign you should evaluate further. The cause may be a temporary condition, a reaction to a drug, an infection, autoimmune disease, bone marrow disorders, or other health issues.

Common causes of low white blood cells

- Medications and treatments: Some drugs suppress bone marrow activity, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, certain antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and immunosuppressants. The chemotherapy-ravages its target cancer cells but also affects healthy rapidly dividing cells, including those in the bone marrow.

- Infections: Certain viral infections (for example, influenza or HIV in some stages) can temporarily lower WBCs. Severe or chronic infections may also impact production.

- Autoimmune disorders: Conditions in which the immune system attacks healthy cells can reduce WBC counts.

- Bone marrow problems: Diseases that affect bone marrow such as aplastic anemia, leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, or certain cancers can reduce the production of white blood cells.

- Nutritional deficiencies: Severe deficiencies in minerals or vitamins (e.g., vitamin B12, folate) can impair bone marrow function.

- Congenital conditions: Some people are born with inherited disorders that affect WBC production.

- Alcohol and certain toxins: Heavy alcohol use and exposure to some chemicals can suppress bone marrow.

- Pregnancy: WBC counts can fluctuate during pregnancy, though persistent severe leukopenia is less common.

Symptoms that might accompany a low WBC count

- Frequent or unusual infections (recurring, slow to heal, or unusually severe)

- Fever or chills, especially with new infections

- Mouth ulcers, persistent cough, or skin infections

- Fatigue, weakness

- Night sweats

- Shortness of breath or chest discomfort during infection

Note: Some people with mild leukopenia have no noticeable symptoms. Regular blood tests are often how the condition is detected, especially during cancer treatment or routine checkups.

What tests your healthcare provider may order

- CBC with differential: The starting test to measure total WBCs and break down the numbers of each type.

- Absolute neutrophil count (ANC): A specific measure of neutrophils, used to gauge infection risk.

- Reticulocyte count and other blood tests: To assess bone marrow function and look for related issues.

- Blood cultures or other infection tests: If you have symptoms of infection, to identify a pathogen.

- Bone marrow biopsy: In selected cases where a problem in bone marrow production is suspected.

- Tests for underlying causes: Vitamin B12, folate levels; liver and kidney function tests; HIV test; autoimmune markers; imaging if an internal cause is suspected.

When to contact a clinician promptly

- You have a fever of 100.4°F (38°C) or higher, or any fever with low WBCs (since fevers can be more dangerous in these cases).

- You develop signs of infection: persistent cough, burning when urinating, redness or swelling, spreading skin infection, or other new symptoms.

- You have chest pain, shortness of breath, severe headache, confusion, or severe fatigue.

- You’re on medications known to lower WBCs and notice new symptoms or infections.

- You have a known diagnosis that affects blood cell production (for example, undergoing chemotherapy or having a bone marrow disorder).

Management and treatment considerations

- Treat the underlying cause: If a medication is responsible, your clinician may adjust the dose or switch drugs. If an infection is detected, appropriate antibiotics or antiviral therapy will be started, sometimes guided by the type of pathogen and the patient’s risk profile.

- Infection prevention: In some cases, doctors recommend avoiding crowds or sick contacts during periods of low WBC counts, practicing good hand hygiene, and sometimes wearing masks during flu season or outbreaks.

- Growth factors: For some patients, particularly those undergoing chemotherapy or with certain bone marrow disorders, medications that stimulate white blood cell production (colony-stimulating factors like G-CSF) may be used under medical supervision.

- Antibiotics and antifungals: If there is an infection or a high risk of serious infection, prophylactic or therapeutic antibiotics or antifungals may be indicated. The choice depends on the specific clinical scenario, including ANC, symptoms, and exposure risk.

- Nutrition and lifestyle: Adequate nutrition, balanced meals, good sleep, and minimizing alcohol intake can support overall health and immune function, though they don’t substitute for medical treatment if a problem is identified.

- Vaccinations: Staying up to date with recommended vaccines can help prevent certain infections, but live vaccines may be avoided in people with certain immune deficiencies. Always discuss vaccination plans with your clinician if you have a low WBC count.

Long-term outlook and prognosis

- The outlook depends on the cause and the severity. Temporary, mild leukopenia caused by a viral infection or a transient drug effect often resolves once the underlying trigger is addressed.

- Chronic or severe leukopenia due to bone marrow disorders, autoimmune conditions, or ongoing chemotherapy requires careful management by specialists (such as a hematologist). Regular monitoring, preventive measures against infection, and tailored therapy aim to reduce risk and improve quality of life.

- Early detection and prompt treatment of infections are critical in people with low WBC counts since infections can escalate quickly.

Preventing infections when you have a low WBC count

- Practice good hand hygiene: Wash hands frequently or use alcohol-based sanitizers.

- Avoid germ exposure: Minimize contact with people who are sick; avoid crowded places during periods of high risk.

- Food safety: Some individuals with very low counts may be advised to avoid raw or undercooked foods and unpasteurized products to reduce infection risk.

- Seek timely treatment: Report fever, chills, or new infections promptly to your healthcare provider.

- Follow medication plans exactly: Take prescribed medications as directed, and don’t stop or adjust doses without medical advice.

Ceftriaxone and the idea of distributors

Ceftriaxone is a broad-spectrum antibiotic used to treat many types of bacterial infections. It isn’t a treatment for low white blood cell counts themselves. Instead, it may be used to treat a bacterial infection if one is present or suspected in someone with a low WBC count, especially if the infection is serious or could become life-threatening. If you’re searching for supplies, you might come across references to ceftriaxone injection distributors. This phrase is about where the drug is sold or supplied, not about managing leukopenia. If you need antibiotics, always obtain them through a licensed healthcare provider who can determine whether they’re appropriate and safe for your particular situation.

Bottom line

- A low white blood cell count signals a potential increased risk of infection and can reflect many different underlying causes.

- If you have a low WBC count, work with your healthcare team to identify the cause, monitor for infections, and pursue appropriate treatment or preventive strategies.

- While antibiotics like ceftriaxone may be necessary in the context of an infection, they do not fix the root problem of low WBC production. The focus is on diagnosing the cause and managing infection risk, through a combination of medications, monitoring, and preventive care.