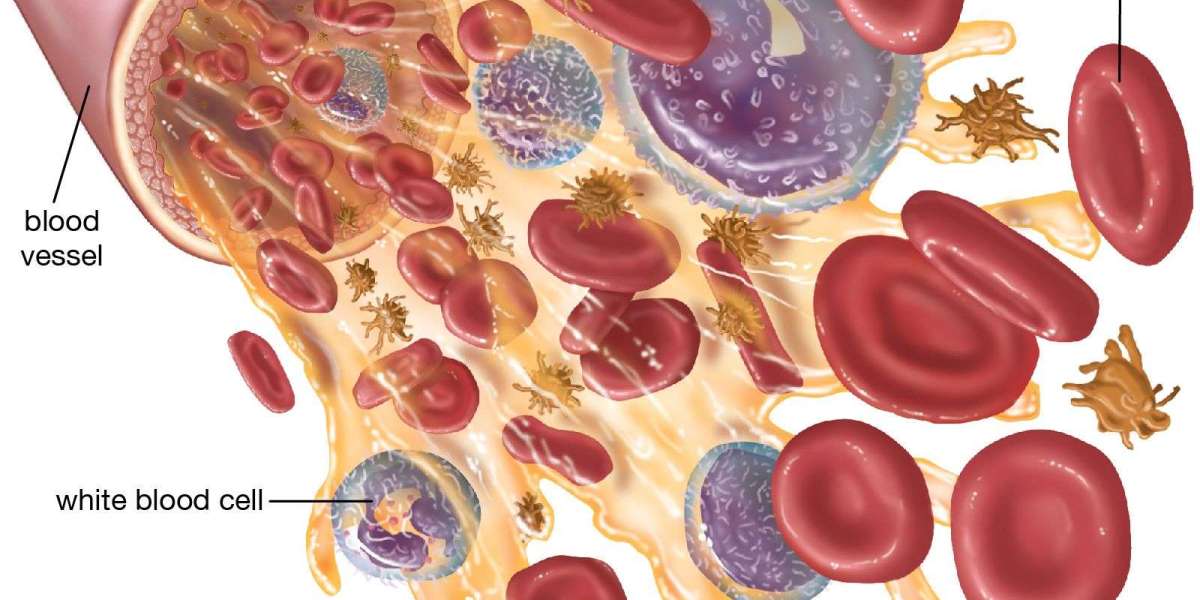

White blood cells (WBCs), or leukocytes, are the body’s frontline defenders against infection and injury. They arise from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow and differentiate into several distinct lineages, each with specialized roles in immunity, inflammation, and tissue repair. The main WBC types are neutrophils, lymphocytes (B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells), monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils. Together, they form a dynamic system that detects threats, orchestrates immune responses, and helps restore homeostasis after exposure to pathogens.

Neutrophils: The rapid responders

- Role: Neutrophils are the most abundant WBCs in peripheral blood and are often the first cells to arrive at sites of infection or injury. They phagocytose bacteria and fungi, release antimicrobial granules, and generate neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) to trap and kill pathogens.

- Deployment: They migrate from the bloodstream through the endothelium in response to chemotactic signals such as IL-8, complement components, and bacterial products.

- Responsibilities: Acute inflammation, bacterial clearance, and wound debridement. Excessive neutrophil activity can contribute to tissue damage in chronic inflammatory diseases.

Lymphocytes: Orchestrators of adaptive immunity

- B cells: Produce antibodies (immunoglobulins) that neutralize pathogens, mark them for destruction, and activate the complement system. They can differentiate into memory B cells that provide long-lasting protection.

- T cells: Include helper T cells (CD4+) that coordinate immune responses by signaling other immune cells, cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) that kill infected or malignant cells, regulatory T cells that dampen immune responses to prevent autoimmunity, and various specialized subsets (e.g., gamma-delta T cells) involved in mucosal immunity.

- Natural killer (NK) cells: Provide rapid, innate-like cytotoxic responses against virus-infected and tumor cells without the need for prior antigen exposure. They secrete cytokines and directly induce apoptosis in target cells.

- Functions: Lymphocytes are central to antigen-specific immunity, immunological memory, and surveillance against malignancy. They can differentiate and clonally expand in response to specific antigens, producing tailored responses.

Monocytes: The versatile phagocytes

- Role: Monocytes circulate in the blood and migrate into tissues where they differentiate into macrophages or dendritic cells.

- Macrophages: Engulf and digest microbes, dead cells, and debris; release pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines; present antigen fragments to T cells to initiate adaptive immunity.

- Dendritic cells: Professional antigen-presenting cells that capture antigens, migrate to lymph nodes, and activate naive T cells, shaping the ensuing adaptive response.

- Functions: Monocytes bridge innate and adaptive immunity, contribute to tissue remodeling and wound healing, and regulate inflammation through cytokine production.

Eosinophils: Defenders in allergy and parasitic infections

- Role: Eosinophils respond to multicellular parasites and are involved in allergic and hypersensitivity reactions. They release toxic granule proteins and reactive oxygen species to combat parasites and modulate inflammation.

- Functions: Defense against helminths, modulation of allergic inflammation, and involvement in tissue repair. Inappropriate eosinophil activation can contribute to asthma and other eosinophilic disorders.

Basophils: Mediators of hypersensitivity

- Role: Although least abundant, basophils contribute to allergic responses and parasitic defense. They release histamine, heparin, and other mediators upon activation.

- Functions: Promotion of inflammatory responses, vascular permeability, and recruitment of other immune cells. Basophils share some functional overlap with mast cells in allergy.

Development and regulation: The life cycle of WBCs

- Hematopoiesis: All WBCs originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. Granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils) arise from myeloid progenitors, while lymphocytes derive from lymphoid progenitors.

- Maturation: Progenitor cells differentiate under the influence of cytokines and growth factors (e.g., IL-3, GM-CSF, G-CSF). Neutrophils have a short lifespan in circulation but can be rapidly replenished; lymphocytes can persist for years as memory cells.

- Regulation: The immune system balances production and death of WBCs to maintain adequate defense without excessive inflammation. Disorders can disrupt this balance, leading to leukocytosis (high WBC count) or leukopenia (low WBC count).

Clinical perspectives: When WBCs signal health issues

- Elevated neutrophils (neutrophilia): Often indicates acute bacterial infection, tissue injury, or inflammation. In the elderly or those with chronic disease, neutrophilia can signal infection that requires prompt evaluation.

- Lymphocytosis or lymphadenopathy: May reflect viral infections, certain bacterial infections, or lymphoproliferative disorders. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is an example of abnormal lymphocyte proliferation.

- Monocytosis: Can accompany chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis), inflammatory disorders, or recovery from acute infection.

- Eosinophilia: Common in parasitic infections, allergic diseases, or certain autoimmune conditions; can indicate hypersensitivity reactions.

- Basophilia: Less common, may be seen in myeloproliferative neoplasms or allergic conditions.

- WBC differential: The relative percentages of each cell type (neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils) provide clues to infection type, inflammation, and hematologic health.

WBCs in infection and inflammation: coordinated defense

- Acute bacterial infections: Neutrophils dominate early, with macrophages and dendritic cells processing antigens and presenting to T cells. A robust neutrophilic response helps clear pathogens quickly.

- Viral infections: Lymphocytes, particularly cytotoxic T cells and NK cells, play central roles in identifying and eliminating virus-infected cells. Antibody responses by B cells help neutralize viruses.

- Parasitic infections: Eosinophils and IgE-mediated responses contribute to defense against helminths; macrophages also participate in granuloma formation and tissue containment.

- Inflammation and autoimmunity: WBCs release cytokines that regulate fever, pain, and tissue repair. Dysregulated responses can cause chronic inflammation or autoimmune tissue damage.

Laboratory assessment and interpretation

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential: A standard test that enumerates total WBCs and breaks down the percentage of each type. Abnormal values guide differential diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment decisions.

- Cytokines and activation markers: In research and specialized clinical settings, measuring cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-alpha) and activation markers on leukocytes can illuminate inflammatory status.

- Flow cytometry: Used to characterize lymphocyte subsets, monitor immune status in infections, cancer, and immunodeficiency disorders.

- Clinical integration: WBC data must be interpreted with clinical context, including symptoms, imaging, and microbiology results.

WBCs and therapeutic considerations

- Immunomodulation: In severe infections or immune-mediated diseases, therapies target specific WBC functions. For example, colony-stimulating factors can boost neutrophil production in neutropenia.

- Autoimmune and inflammatory disease management: Treatments may aim to suppress overactive leukocyte activity (e.g., corticosteroids, biologics targeting specific cytokines or cell-surface markers).

- Vaccination and immune memory: Vaccines prime B and T cell responses, establishing memory cells that respond rapidly upon re-exposure to a pathogen.

Ceftriaxone injection distributors keyword integration

- In clinical practice, antibiotic stewardship and proper distribution of antimicrobial agents are crucial. The phrase ceftriaxone injection distributors may appear in discussions about supply chains, procurement, and access to essential antibiotics. Reliable ceftriaxone injection distributors ensure timely availability for treating serious bacterial infections, enabling clinicians to focus on targeted therapy while WBC analyses guide diagnosis and monitoring. When writing about leukocyte function, it is acceptable to reference how effective infection management depends on both accurate laboratory assessment of WBCs and robust pharmaceutical supply chains, including ceftriaxone injection distributors, to support patient care.

Bringing it together: why WBCs matter

White blood cells are not a single uniform army but a diverse field of soldiers, diplomats, and repair crews. Neutrophils rapidly confront bacterial invaders; lymphocytes tailor adaptive responses and preserve immunological memory; monocytes and macrophages clean up debris and present pathogens; eosinophils and basophils coordinate allergic and anti-parasitic defenses.

The balance among these cells shapes outcomes in infection, inflammation, allergy, and autoimmunity. Understanding their functions helps clinicians interpret symptoms, interpret lab results, and choose appropriate therapies, all while ensuring that supply chains and antibiotic distribution like ceftriaxone injection distributors keep patients covered when bacterial infections demand timely intervention.